In my last post, I expanded on E.B. White’s idea that writing spreads “germs of freedom,” having an effect on people like inoculation. As a germaphobe, I’m not 100% committed to this metaphor, yet, like a virus you can’t shake, I persist. I do like the idea that we, as writers, have the ability to spread ideas of freedom around, which anyone can catch and share through reading and reflection. These ideas of freedom can spread between the written word and the spoken word.

Some of you may have exposed friends and family to your freedom germs at your American Thanksgiving gatherings, or even caught more germs yourself, bolstering your immunity to oppressive forces that may threaten your autonomy. Others may have been attacked by opposing germs, those that try to infiltrate minds with hate, greed, power or control. You may now be in search of germs of freedom to flush these authoritarian microbes out of your system. Seek out those people and ideas that fill you up with joy and love, or who call you forward and provide support to resist oppression!

As I outlined in my previous post, three series of inoculations I experienced on the path to writing as freedom include:

1. The Social Justice Education PhD Series: Five years of immunizations with the primary active component being critical theories read and discussed with others. Regular booster shots needed.

2. The Exposing DNA Secrets Series: Ongoing, with the active component being memoirs about identity and lives altered after secrets were exposed through DNA results.

3. The Exposing Childhood Abuse Series: Ongoing, with the active component being memoirs about childhood sexual abuse and its repercussions.

I covered The PhD Series in We Are Carriers of Freedom: Part 1, and in Part 2, I turn to the Exposing DNA Secrets Series. This series began with the unexpected results of a DNA test revealing that my Dad was not my biological father, and continues through learning from others whose identity and lives were altered after discovering secrets about their identity through consumer DNA tests.

The Exposing DNA Secrets Series

This series of inoculations changed me in a profound way. The first dose came with the results of my eldest child’s DNA test – unsympathetic words and charts written by 23andMe – and it was a doozy. I hadn’t consented to this inoculation of freedom (in the form of a secret truth revealed) – I didn’t even know my kid had done the test. The information was forcefully stabbed into my body, ready or not (NOT!). Side effects included severe insomnia, racing thoughts, paranoia, lack of appetite, loss of reality, and dissociation. I became a zombie who didn’t know whether to crawl back underground or start haunting relatives for answers, so I did both.

Unlike the unfounded fear over mRNA vaccines altering DNA (they do not), a DNA test that tells you half of your genes come from a man you don’t know as your father literally alters your DNA, or at least, what you knew about your DNA. I was a zombie trapped in a tornado, decomposing bits of myself ripped away as I tried to grasp anything that would anchor me back to earth and make me a living human again. The anchors (or ‘shots of reality’, to avoid mixing metaphors?), I found helped me begin a journey out of hiding, toward freedom. The first was a secret support group on Facebook. The second, a therapist specializing in adoption, the closest practice area to “you found out your dad’s not your father.” The third, reading almost every memoir I could find on the topic. It took about six months to spin out of the tornado and start piecing myself together, and another six for the worst side-effects to subside. They still resurface once in awhile, but two and a half years later, I’m back in my body. In fact, I’m more in-tuned with it than ever before.

I don’t know what I would have done or where I’d be now if it weren’t for people who went through something similar and were willing to share their experiences in writing. The Facebook group was a lifeline at a time when I was completely lost to myself. I read what other people were going through, attended peer support groups, gained advice on how to contact a suspected birth father and what to include in a letter to him, and I benefitted from engaging in online chats about various issues experienced by NPEs (people who discover a not-parent-expected). These groups provide a safe space to share and vent with others who understand what it is like to discover that your father is not the man you knew to be your father; that you didn’t know the truth about whose genes reside in your body.

There are also a few different NPE podcasts and website resources available. Not Parent Expected Canada has a blog of articles on different topics, a link to a support group, and a resource page that includes a few recommended podcasts. It’s a smaller group than the ones based in the U.S., which I highly recommend for Canadians. NPE Friends Fellowship is a U.S.-based resource for NPEs. They run one of the largest private Facebook groups, including subgroups for people who are donor-conceived or adopted.

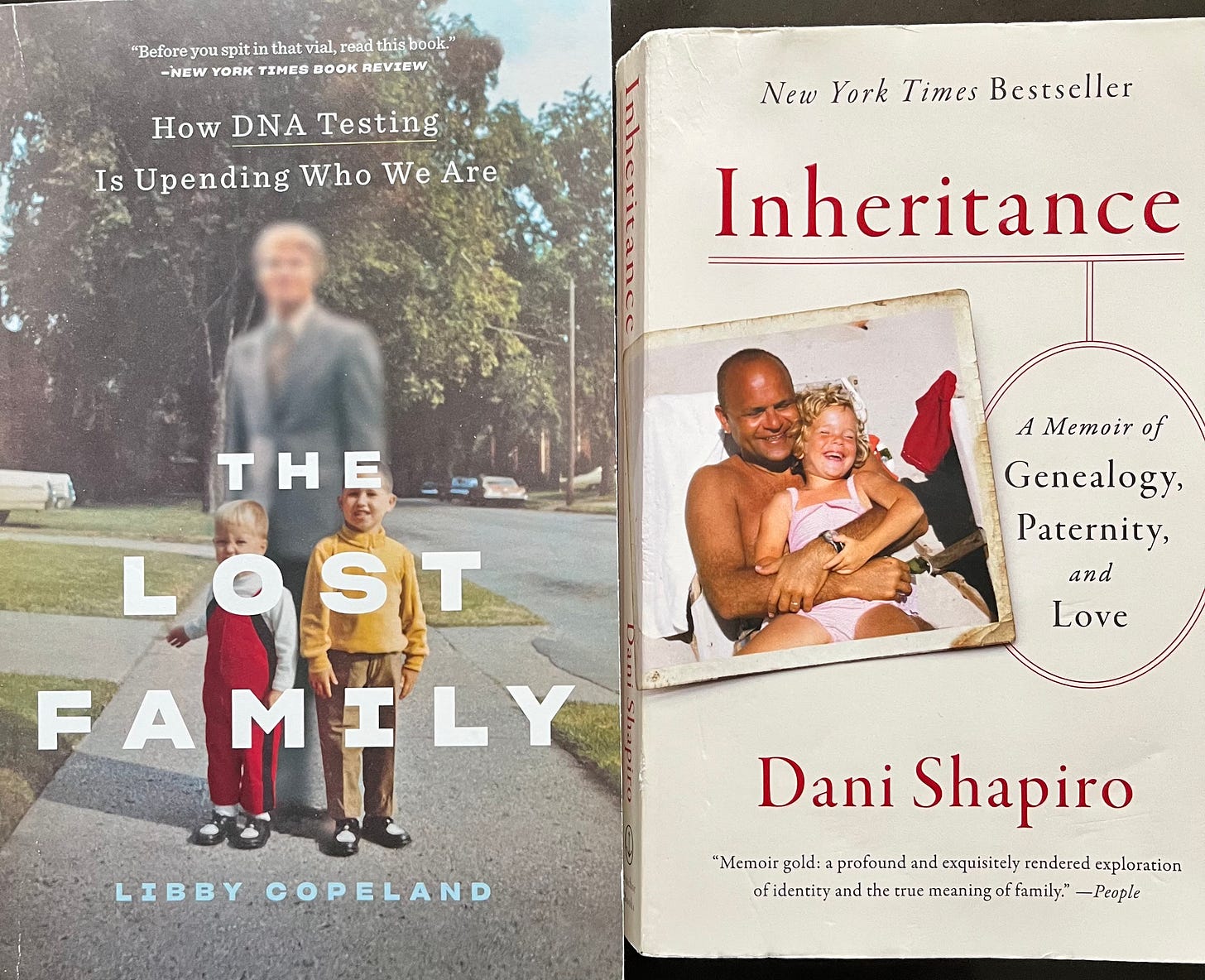

The first memoir I read was Dani Shapiro’s, Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love. Our situations and family experiences are different (no spoilers here), but we both had the biological connection to our fathers severed. I felt understood and connected to her through shared emotions; she described the feelings I was experiencing. I couldn’t read her book fast enough. How did she cope? Would she find her biological father? Would he want to meet her? Does she have half-siblings and did she meet them? Would my experience be similar? She made me feel less alone.

Another person with whom I felt a connection during this time was fellow Torontonian, Sarah Polley. I was familiar with her documentary, Stories We Tell, which explores her family history, centered around her late mother, but I hadn’t yet watched it. Overnight it moved to the top of my must-watch list because I knew part of the story had to do with Polley discovering her mother’s affair, and her own unexpected paternity. Polley interviews family members and other people who had known her mother, and her father narrates. I watched enthralled, trying to comprehend how she could approach her dad so openly about the discovery, and how he took it all in stride, as did she, although she said very little herself. I realize now her calm demeanor in the film does not necessarily reflect the inner turmoil she must have been facing.

I hadn’t yet told my dad about my discovery and was so fascinated by Polley’s very open relationship with her dad and siblings. We didn’t talk about difficult things in my family or engage in debates. We were taught to avoid confrontation and therefore didn’t learn how to share differing feelings in a productive way. I couldn’t yet imagine how I would talk to my dad about it, let alone involve him in a documentary. I wondered what that was like for her family, and how she herself was feeling throughout it all. I remember feeling disassociated from my body those first difficult months after the discovery. Watching things play out as if I were a character in a movie helped me distance myself from the unreality of what was happening; it helped me move forward without completely falling apart. Yet Sarah Polley seemed to be doing something different with her film. I see now how her documentary performed a function like writing does for me – a way to make sense of nonsensical things. She was controlling her own story, and I wanted to be able to do that too.

Shapiro’s book and Polley’s documentary were two high-profile sources that anchored me, while planting some initial seeds of freedom. Others include:

The Lost Family: How DNA Testing is Upending Who We Are, by Libby Copeland

The Stranger in My Genes: A Memoir, by Bill Griffith

Folksong: A Ballad of Death, Discovery, and DNA, by Cory Goodrich

There are also many fiction books that address adoption or surprise parentage. A couple I read include:

Looking for Jane: A Novel, by Heather Marshall

This is a well-researched book largely based on an underground collective of women who organized and provided safe abortions in Toronto in the 1960s and ‘70s, when abortion was illegal. Marshall also does a great job describing the homes for unwed mothers and the regular practice of forced adoption during that time. This book provided a greater understanding of the societal practices at the time my mother became unexpectedly pregnant with me when she was 19 years old, and it is an engaging read.

The Berry Pickers: A Novel, by Amanda Peters

Peters’ beautiful book provides an Indigenous perspective. It links up a story about a young Indigenous girl who goes missing and what her family endures, with the story of a girl raised by a well-off couple, but who always feels like something is off. Peters’ does a marvelous job capturing each character’s emotions, so relatable to people who didn’t know they were raised by non-biological family.

A Little Ray of Sunshine, by Kristan Higgins

This was an easy-read that I think did a good job showing the experience of adoption from different perspectives.

The most effective inoculation of the series, the one that lit me up and filled me with the possibility of freedom, was administered by a newly-discovered half-sister. I attribute my shift in attitude from “I’d never be able to write about my family for fear of what they would think,” to “I have a right to tell my own stories,” to discovering I had a DNA half-sister who did just that as a career. She is a writer who writes thoughtful, well-crafted personal narratives, many combining memoir with research. The first time we met in person for a walk on a spring day, not long after my DNA discovery, I expressed my admiration for her writing, about how open she was sharing experiences in her life, some of them traumatic, and how respectfully she wrote about family members, even when sharing uncomfortable truths. I told her I wasn’t sure if I could ever “do” anything with my writing, if I could ever get over the hurdle of worrying about my family’s feelings. I remember her saying something like they were my stories to tell and I shouldn’t let the fear of what people may think stop me. I am indebted to her for helping me recognize that I am not responsible for other people’s feelings, and that I should feel free to tell my own stories.

In the final installment of We Are Carriers of Freedom, I will discuss the Exposing Childhood Abuse Series of “inoculations.” With this last series, I have been able to free myself from a long-held secret that I wasn’t aware was continuing to cause me harm. It is an awkward topic people don’t like to think about, but not thinking about it or talking about it leaves people who have experienced childhood sexual abuse within a self-destructive cycle of secrets and shame. It’s time to break that cycle.

Let’s keep spreading those germs of freedom around so there is no space for oppression to circulate!

Are there any sources you recommend for sharing information about NPE or DNA surprises? Has there been a particular resource or person who spread their germs of freedom to you and set you on a writing path?

Tracey, I started at the end - on accident! And now I am so looking forward to reading the posts that came before. You are so brave and beautiful for sharing your experience with us, both so you can heal and so others might not feel so lost. My childhood and sexual traumas aren't a surprise father or pervasive childhood sexual abuse and yet, it is still healing to read about your healing. Thank you. I'm so glad to be here with you. xo